An Idea is a Work of Art

Collage, imagining new worlds, and Jack Whitten's spiritual vision

Friends,

I first discovered the album Purple Moonlight Pages in November on Aja Monet's playlist the “poetics of listening” (what a great phrase!). I was walking through the neighborhood, trying to let my eyes and brain rest from a screen-heavy week, when R.A.P. Ferreira helped me process my own creative life in his song “Cycles.” At a break between verses, he says that art is a “sacramental human activity” where we go to the “frontiers of consciousness and report back what's there.” I’ve since learned he’s quoting Susan Sontag, right in the middle of a rap song on the ways art can respond to social crises:

At the end of the world, we was fightin' back with brushes and pens

We decided that the suffering should end, no matter how good it feels

Wooden shields ain't stoppin' bullets

So we dropped those, quit lyin' to ourselves

Started writin' poems, got stronger by ourselves

Kinship bein' the hunger that we felt...

I love the way all of this co-exists in the same song: a rap artist and media theorist responding to today’s injustice. There's a different kind of kinship there, a dialogue across time as he collages together fragments into one work of art. At the end of the song, he offers this dedication:

Peace to the eternal spirit and soul of the grandmaster Jack Whitten. An idea is a work of art. From Chicago, Illinois to Bessamer, Alabama. An idea is a work of art. Peace, peace, peace, peace...

Wait—who is Jack Whitten? And what does it mean that an idea can be a work of art? If R.A.P. Ferreira felt strong enough about him to dedicate a song to the artist, then I wanted to know why. We’re in the middle of a month-long series on Black history in these Still Life letters, so I took his reference as an invitation to go back in time. This week, I did some digging on Jack Whitten.

I watched a bunch of interviews, and I quickly saw some resonance between these two men: a deeply felt creative integrity, a shared approach of making meaning out of fragments of ideas, eccentric spirituality, and an authoritative point of voice burnished from their lived experience as Black men in America. One's a rap artist, one's an abstract painter, and both approach artmaking to make space for new ways of thinking and new social possibilities. Ideas as works of art.

That intersection of art and possibility is deep in the DNA of Still Life, but instead of writing more about all of this, I wanted to get out of the way. I wanted you to hear from Jack Whitten directly using the same creative approach they both share: collage, pulling together fragments and making new meaning.

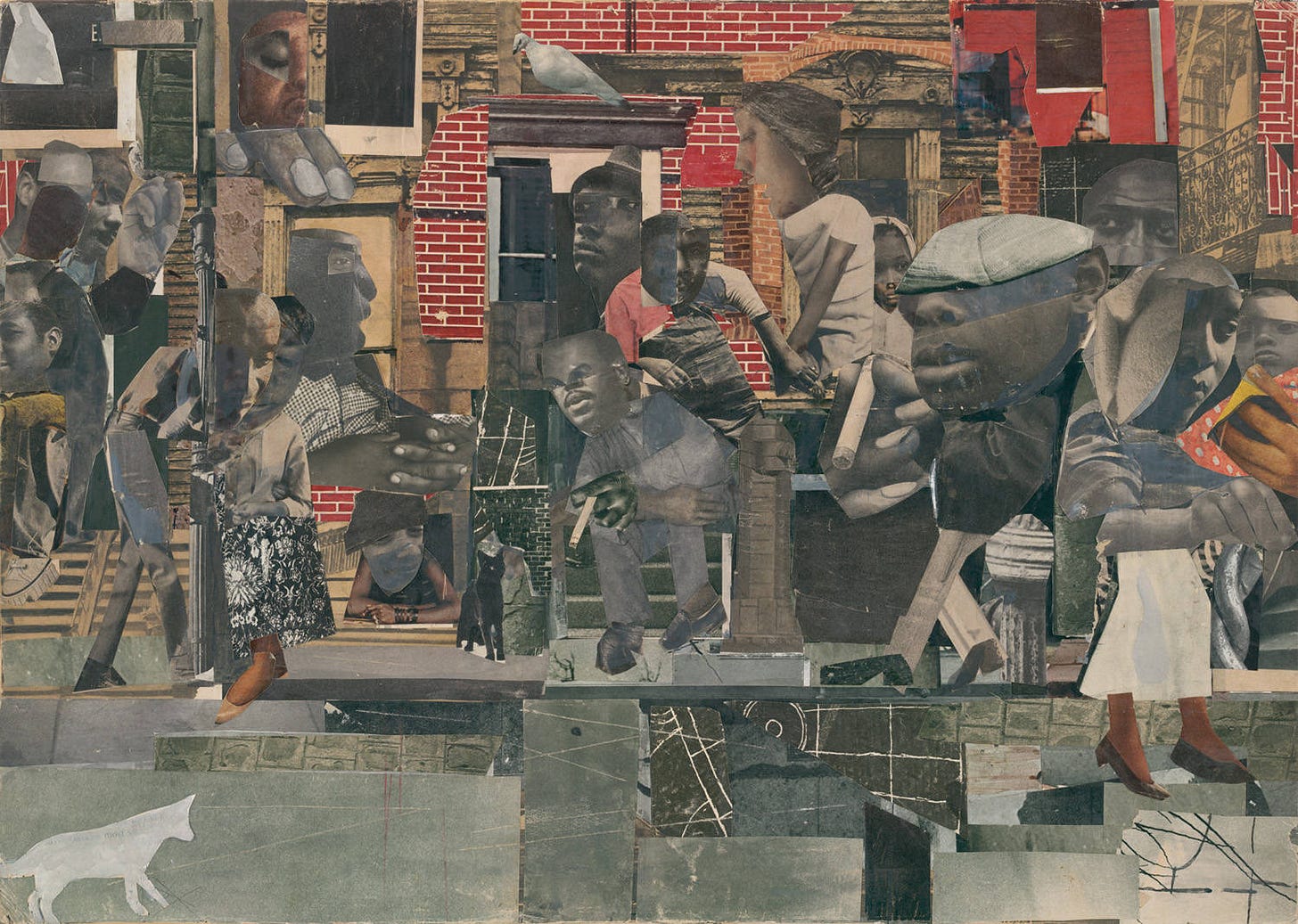

So I transcribed the interviews I watched, printed them off, and cut them all together into a “collage essay” (Here are some process photos). I didn't add a single word—just spliced together Jack’s ideas across many interviews into one place. And check this out: a day after finishing this process, I discovered that there's actually a traveling exhibition up right now on collage and the Black experience. Kismet! Lanecia Rouse Tinsley, an artist in the show, put her creative approach this way:

I'm using these storied and textured materials, layering them up, and then excavating in the work—pulling and adding and working to find some kind of beauty and harmony with all the broken pieces and the fragments. That's what I do in my collage work, and I think that's a really important work as we being to imagine possibilities for new worlds.

Imagining possibilities for new worlds. One of the ways we can do that is to dig around in the past, listening deeply to the people who've come before us, and find new ways to stitch their points of view into our own. Collage as an art and social practice, a way to build new ways of thinking. Or as Jack Whitten says below, “My paintings teach me how to live. They inform the structure of my worldview.” And he built that structure throughout decades of painting, a bridge between Black history and today. By listening deeply to his words and engaging his ideas, it might teach us how to live too.

Take care,

Michael

A Reflection on Art and Spirit by Jack Whitten:

I grew up in Bessemer, Alabama. Everything was segregated then. Transportation, the buses. 1960s, as you know here in America, was difficult times. The Civil Rights Movement was raging, the Vietnam War, the identity issue of being Black in America—what do you do with that?

I always did art. I always did painting since I was a kid, but it was not encouraged. The theory being that it's good for a hobby but you couldn't make a living out of it. Lucky for me, I graduated with good grades. I went to Tuskegee.

I met Dr. Martin Luther King in 1957 in Montgomery during the bus boycott when I was a freshman. I believed in what he had to say and his theory of nonviolence. You know, young people, we absorb things. When you meet someone like Martin Luther King, he had something about him—boy you would have to be damn unsensitive to not be attracted to what came out of him! Tuskegee did not had an art program so I went further south to Baton Rouge, Louisiana to study art at Southern University.

I was there for a year, and things went well until I got involved politically with the demonstrations. We organized a big civil rights march that went from downtown Baton Rouge to the state office building. It was that march, which turned vicious and violent, that drove me out of the South. That march changed me politically forever.

The fall of 1960, I took a greyhound bus from New Orleans to New York City to take the test at Cooper Union, and I was accepted. I studied art, painting. In 1960, the scene was open—Bill de Kooning would talk to you! Some of the first people I met were Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, and Jacob Lawrence.

But I'm not a narrative painter. I don't do the painting being an illustration of an idea, I don't do that. It's all about the materiality of the paint. I felt I had a better chance getting across what I was feeling through abstraction. I refer to this as elemental matter. With this, I can build anything I want. As an abstract painter, I work with things that I cannot see. We can only feel its presence.

I'm after a worldview. One of the most of important elements in it is some form of spirituality that accomodates science and technology. I believe that we are in a spiritual dry land. The old symbols that we had from previous established religion they're not workable anymore for this society. We have to invent new symbols. And that's where the spirituality comes in. You know, I've been working close to 60 years now but there's a lot out there I don't know. We only know probably one percent or less than one percent of the matter in the universe. The whole cosmos! Think about that! Where's the rest of it? What is it?

We know the present times are pretty bad. And if the type of rhetoric we're having to deal with every day escalates, my thinking is that there has to be some point where it's going to explode even more so. Some people say, “I hope it doesn’t.” Hope helps, but hope is not enough. It really isn't. There's something global going on that comes out of hate. And that's frightening for us to admit that what we're experiencing is not just regional, and it goes beyond just being Black. For me, what's happening today is nothing new for me—I was born into it. Remember I was born in 1939 Bessemer, Alabama. Deep south, the height of segregation. I was born in what I call “American apartheid.” So I've always had a sense of purpose right from the beginning. The political is in the work. I know it's in there, because I put it in there.

I am the one who has the right to hate, I am the one who has the right to kill, but I don't. Because I made a pact with myself that I was not going to live that way. And I suggest to all people, make a contract with the universe of how you want to live and what kind of person you want to be. Because there's a level out there of being human—that's the only thing we got left. Without that pact that each one of has to make about what kind of people we want to be, I mean I don't see any hope. I really don't. I made the pact, and I suggest others do the same.

It would be foolish of me to say that bitterness does not exist. One does not that easily wipe away bitterness. Coming out of Alabama and what I experienced—and I haven't told you all of it—I realized that there came a point in my life that the decision was mine: I had to make a choice of what I wanted to do with my life and what kind of person I wanted to be. So even after all these years and all these experiences, I signed a contract with the universe that I was not going to hate. It's a contract between spirit and matter, that's what it is. That was my decision.

That's why I say that art runs parallel to religion. It's an act of faith. My paintings teach me how to live. They inform the structure of my worldview. That's what abstraction does for me. It's stuff I've been thinking about, been piecing it together, a little piece here and little piece there. In truth, it becomes the reason I get out of bed every morning. I don't make that difference between art and life. First there's life, then everything else happens inside of that. I came to art, I say, through revelation.

“The Truth” by Ted Joans

If you should see

a man

walking down a crowded street

talking aloud

to himself

don’t run

in the opposite direction

but run toward him

for he is a POET!

You have NOTHING to fear

from the poet

but the TRUTHThe “collage essay” is built from the following interviews that Jack Whitten filmed during the last few years of his life:

Jack Whitten – “The Political is in the Work” (Tate Museum)

Jack Whitten: In the Studio (Hauser & Wirth)

Artist Jack Whitten On A Pact He "Made With The Universe" (Blanton Museum of Art)

Jack Whitten: Five Decades of Painting (Walker Art Center)

An Artist's Life: Jack Whitten (Art21)