Friends,

This month we’re searching for poems that start with simple fruits and veggies and spiral out into deeper questions about life. So far we’ve looked at radishes and grapefruit, and I’m excited to share today’s poem about a tomato. I had a completely different essay started, but after I found Natasha Rao’s stunning poem this week, all sorts of connections sparked off in my brain. I had to share it with you. She contrasts the anxieties and fears of a human life with the vivacious life of garden tomatoes, trembling in sunlight, and I hope you feel inspired by it just as much as I do.

Take care,

Michael

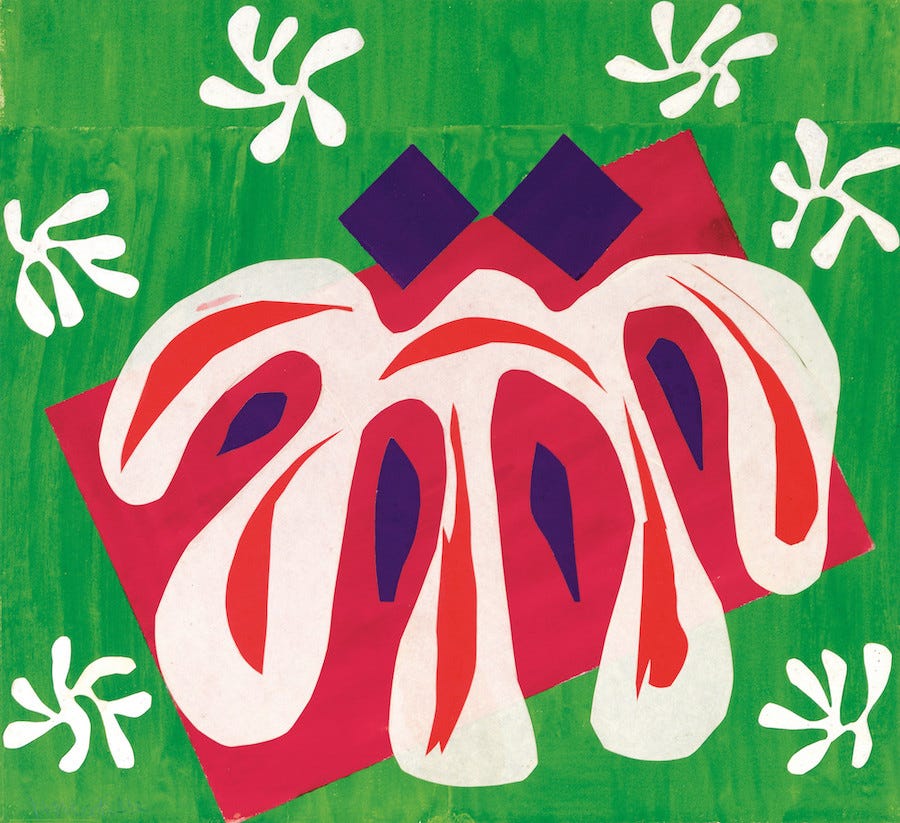

p.s. This week is a good example of why I like writing Still Life. The internet is vast because human life is vast. So why not look for connections among a Matisse painting and a poem by a first-generation Indian American poet and a Catholic nun-artist and a folk song by the director of a California Buddhist monastery? To paraphrase Whitman: “we are large, we contain multitudes.”

“In my next life let me be a tomato” by Natasha Rao

lusting and unafraid. In this bipedal incarnation

I have always been scared of my own ripening,

mother standing outside the fitting room door.

I only become bright after Bloody Mary’s, only whole

in New Jersey summers where beefsteaks, like baubles,

sag in the yard, where we pass down heirlooms

in thin paper envelopes and I tend barefoot to a garden

that snakes with desire, unashamed to coil and spread.

Cherry Falls, Brandywine, Sweet Aperitif, I kneel

with a spool, staking and tying, checking each morning

after last night’s thunderstorm only to find more

sprawl, the tomatoes have no fear of wind and water,

they gain power from the lightning, while I, in this version

of life, retreat in bed to wither. In this life, rabbits

are afraid of my clumsy gait. In the next, let them come

willingly to nibble my lowest limbs, my outstretched

arm always offering something sweet. I want to return

from reincarnation’s spin covered in dirt and

buds. I want to be unabashed, audacious, to gobble

space, to blush deeper each day in the sun, knowing

I’ll end up in an eager mouth. An overly ripe tomato

will begin sprouting, so excited it is for more life,

so intent to be part of this world, trellising wildly.

For every time in this life I have thought of dying, let me

yield that much fruit in my next, skeleton drooping

under the weight of my own vivacity as I spread to take

more of this air, this fencepost, this forgiving light.“In my next life let me be a tomato”

lusting and unafraid. In this bipedal incarnation

I have always been scared of my own ripening,

mother standing outside the fitting room door.

Starting from the title itself, the poet sets up a comparison. This poem won’t just be about tomatoes but a contrast between her own life and what she can learn from these tomato-lives. “Scared of my own ripening,” is such a great line, reminding me of the anxieties that start to creep in with middle age—but she places that fear in an early childhood memory. Growing up is hard because growing is weird. Our bodies are in constant motion, constant change, and that can be an overwhelming thing (have you ever stared at your hand long enough and thought what IS THIS THING?? Oh, just me? Moving on…). It’s also worth pointing out “lusting and unafraid,” descriptions we usually don’t associate with veggies. But with careful attention she finds a carefree freedom in the life of the tomato plant she wants for herself—if not in this life, then maybe the next.

I only become bright after Bloody Mary’s, only whole

in New Jersey summers where beefsteaks, like baubles,

sag in the yard, where we pass down heirlooms

in thin paper envelopes and I tend barefoot to a garden

that snakes with desire, unashamed to coil and spread.

Now she starts to paint a landscape scene: a garden. Maybe it’s a family plot, some land in the backyard. In any case, being in that garden is where her anxieties and fears about her own “ripening” fall away. She becomes “bright,” surrounded by the different varieties (Bloody Mary’s, beefsteaks) hanging around her like baubles. I love the description of seed packets as “heirlooms / in thin paper envelopes” and how it gives those humble containers a sense of heft and sacredness. And then—in a reversal of Eden—the poet is barefoot in a garden snaking with desire, “unashamed to coil and spread.” Snakes, of course, are a common image of something or someone not to be trusted, something dangerous, the cause of sin. But here, the garden itself “snakes.” It spreads and grows, tomato vines coil, and the barefoot poet completes a picture: all is right in the world in a backyard garden. Surrounded by greening life, shame and anxiety can fall away like husks.

Cherry Falls, Brandywine, Sweet Aperitif, I kneel

with a spool, staking and tying, checking each morning

after last night’s thunderstorm only to find more

sprawl, the tomatoes have no fear of wind and water,

they gain power from the lightning, while I, in this version

The poet continues listing specific tomato varieties (some cherry-sized, some wild-ridged and bigger than your hand), and kneels. Note the line break here. On the first line we’ve got “I kneel" and only when our eyes reset to the next line we’ve got “with a spool.” THIS IS WHY POETRY IS COOL, PEOPLE. That gap, that slight little speed bump is on purpose: kneeling is a deeply human act of recognition. Whether in ceremony or ritual, kneeling says “I humble myself in response to what’s in front of me.” That meaning is certainly present here, tied then to….a spool of garden thread. Sacred and mundane, brought into focus with a line break. Also, if you read Mark Doty’s poem on radishes, did you notice the similarities here? Doty calls radishes “bundles of thunder,” and here Rao says tomatoes “gain power from the lightning.” Just some nice intertextuality there, do with it what you will.

of life, retreat in bed to wither. In this life, rabbits

are afraid of my clumsy gait. In the next, let them come

willingly to nibble my lowest limbs, my outstretched

arm always offering something sweet. I want to return

from reincarnation’s spin covered in dirt and

Whew, the contrast of “wither.” Tomatoes grow unafraid by storms, take in the power of lightning through alchemical process of gardens, and the poet? Retreats to bed. Or you might say “retreats to the couch for binging beer and TV after a stressful day of work.” Or maybe “retreats to listening and not risking sharing an opinion at a dinner party” or “retreats into a mental storm of oh-my-god-did-I-say-that-they-hate-me thinking.” Take your pick, we humans have many time-tested strategies of withering. But no: the tomato! What if we could be like that instead? Not clumsily self-centered, but open and outstretched—so grounded in ourselves that even animals do a double take and think “oh ok, they’re safe and interesting and willing to share something beautiful with me.” This poet wants to return in another life like this, but dammit I’d like that now please.

buds. I want to be unabashed, audacious, to gobble

space, to blush deeper each day in the sun, knowing

I’ll end up in an eager mouth. An overly ripe tomato

will begin sprouting, so excited it is for more life,

so intent to be part of this world, trellising wildly.

And now the list of tomato varieties has become a descriptive list of qualities that tomatoes and a grounded life share: unabashed (to be “abashed” originally meant to spiral into confusion after a sudden onset of negative emotions—so…the opposite of that), audacious (brave, bold, daring, courageous, unashamed), to gobble space (what a playful contrast with being afraid to “take up space” in the world). And then, even when ripening takes its natural course in death—the tomato still sprouts more, “so intent to be part of this world, trellising wildly.” How do we live like that? How do we grow that kind of leafy, fragrant life for ourselves? There’s acceptance here of all of life’s cycles, pressing into each stage with as much generosity and fearlessness as possible.

For every time in this life I have thought of dying, let me

yield that much fruit in my next, skeleton drooping

under the weight of my own vivacity as I spread to take

more of this air, this fencepost, this forgiving light.

The poet continues her karmic interpretation of the tomatoes (the cycles, the reincarnation) and wants to build up good karma in the next life: for every thought of death, may my next life be that much more alive. I don’t know much about the next life, but I do want this “vivacity” in this one. And then the last lines, good grief. “I spread to take / more of this air, this fencepost, this forgiving light." These short lines gather up all the themes of the poem, the imagery of tomato and gardens and human, and end in “forgiving light.” There’s no strain and struggle here—just a desire to be heliotropic, to turn toward light, to cultivate the right kind of life to receive it well.

Bonus section! Long-time readers will know that Corita Kent is kind of a patron saint of Still Life. Writing about Natasha Rao’s tomato poem reminded me of Corita’s artwork “the juiciest tomato of all,” a 1964 serigraph that caused quite a controversy between the archbishop and Immaculate Heart College where she worked. In the print, she describes the Virgin Mary as a “juicy tomato,” common 60s lingo for being a lil’ hottie. The conservative archbishop was incensed, tried to limit her influence, and their years-long battling ultimately led to Corita rejecting the habit, leaving the Catholic Church, and moving to Boston. UGH, a tragic story (I wrote about it here), but what would’ve happened if the archbishop paused, leaned in, and took a closer look at the serigraph? He might have discovered a handwritten essay on sensuality, food, and the power of the Eucharist in an advertising-drenched culture. It’s by Corita’s friend, the Pasadena poet and therapist Sam Eisenstein (b. 1932), and she transcribed the whole thing on the print. It’s hard to read, so I tracked it down and share it with you here:

The time is always out of joint... If we are provided with a sign that declares Del Monte tomatoes are juiciest it is not desecration to add: “Mary Mother is the juiciest tomato of them all.” Perhaps this is what is meant when the slang term puts it, “She's a peach,” or “What a tomato!” A cigarette commercial states: “So round, so firm, so fully packed” and we are strangely stirred, even ashamed as we are to be so taken in. We are not taken in. We yearn for the fully packed, the circle that is so juicy and perfect that not an ounce more can be add.

We long for the “groaning board,” the table overburdened with good things, so much we can never taste, let alone eat, all there is. We long for the heart that overflows for the all-accepting of the bounteous, of the real and not synthetic, for the armful of flowers that continues the breast, for the fingers that make a perfect blessing. There is no irreligousness in joy, even if joy is pump-primed at first. Someone must enter the circle first, especially since the circle appears menacing. The fire must be lit, a lonely task, then it dances. The spark of flame teaches one person to dance and that person teaches others, and then everyone can be a flame. Every one can communicate. But someone must be burn.

Perhaps everyone who would participate entirely in the dance must have have some part of himself burned and may shrink back. They look for some familiar action to relate to. There is too yawning a gulf between oneself and the spirit, so we turn to our super-markets, allegories; a one-to-one relationship. You pay your money, you get your food, you eat it, it's gone. But intangibly, during the awkward part of the dance, with the whole heart not in it, with the eye furtively looking out for one's own ridiculousness, allegory becomes symbol, wine becomes blood, wafer flesh and the spark flames like bright balloons released, and the “heart leaps up to behold,” and somehow we have been taken from the greedy signs of barter and buying, from supermarket to supermundane. We have proceeded from the awkward to the whole. The rose of all the world becomes, for awhile, and in our own terms, the "pause that refreshes," and possibly what was a pause becomes the life.

The Listening Heart: Corita Kent’s Reforming Vision

Hi Michael, I've noticed the last few posts include dissecting poems. It's not my thing, but appreciate it if it is helping you. I'd rather read your poems.

Yessss. And of course, Corita. This fall, a friend and I were looking at metaphors for growth and change. Ripening was such a vibrant, lush one— and this line "I have always been scared of my own ripening" has lingered with me sense. Lovely exploration, M.