Your Soul Writes Come Home

Reckoning with the Country Music Hall of Fame—and finding a larger musical world

“Good evening, thank you for joining us. This transmission is addressed to the fence-building nihilists. Your soul writes, ‘come home.’ Abandon them outdated strategies, namely hatred. Exile is no place for a person, or your compassion. Come home. Good evening. Good evening.”

—R.A.P. Ferreira, “DECORUM,” Purple Moonlight Pages

Friends,

Last time Lindsey and I were in Nashville, I made sure to take her to the Country Music Hall of Fame. We were in my old stomping grounds, and more than just a museum it felt like a place to explain a part of myself. To show some civic pride in Music City, a hometown that I carried with me to Los Angeles and still carry now as I write to you in Minneapolis.

Nearby the museum there’s a new symphony hall and a new convention center (with a sloping guitar-shaped roof, of course). A few blocks away is the Ryman Auditorium—the red-bricked “Mother Church of Country Music” that hosted the Grand Ole Opry for decades. And then there’s Broadway. The street slices across downtown with honky tonk bars and neon signs lining both sides, country music spilling out onto the sidewalks. Broadway is less history and more musical myth. Growing up, we’d easily see more cowboy boots clomping down that street in a day than we saw in a whole year.

With distance and time though, my sense of this history has gotten more complicated and, truthfully, I was a bit wary of going back to the Hall of Fame. For starters, did you know that for decades, the Grand Ole Opry featured Jamup and Honey, the “well-known and loved blackface comedy routine?” I sure didn’t. I never heard of this growing up—even though my fourth grade class play-acted on a replica of the Opry stage. We dressed up as Hank Williams and Minnie Pearl with her straw hat, but no one mentioned the famous blackface routines, why it was harmful, and why it seemed we just shuffled it under the rug.

I also went back to that museum with an old watercooler conversation ringing in my ears. My friend Aaron and I took a work break and walked across campus to a coffee shop. He told me what it felt like to be in a class where all the required books were by white males and the books for “further reading” were by people of color: “It felt like if these books are optional, then my history is optional,” he told me. “And if my history is optional, then every student is being trained to go out into the world with an incomplete story.” I felt, then and now, that even though I didn’t make the syllabus my own ignorance wasn’t helping the situation.

And I also went back to that museum with the real story of how Nashville got called “Music City” in the first place. Do you know this? It’s not because of country music—it’s because of Black spirituals. It’s because of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a student choir from the historically Black Fisk University who performed spirituals and slave songs, one of the first examples of American music this country introduced to the rest of the world. Story has it that after they sang for Queen Victoria in 1873, she said they must be from a “city of music” because of their talent. Y’all. I’m from Music City, and I was wrong about this history until my thirties. I thought it was because of country music! And, I’m ashamed to say, I’ve never even heard the Singers in concert or visited the historic campus, even though they’re still singing, over a century later, in my own hometown. How did I miss this beautiful culture and history literally down the street from my own home?

So I went back to that museum, ready to learn and very aware that there were whole histories I was missing. How did that happen? Where were the gaps in the story? I found them, starting right there in the first room. On one of the first placards, the museum framed country music as the first real American music, blending earlier styles like madrigals and hymns in the Appalachian hills. And then, after quick mention of blackface minstrelsy and the banjo (an African instrument), there it was: the history of splitting genres: “hillbilly records” and “race records.” Both an expression of the segregation of the time and a deepening of it, record execs built a fence right through these new American musical idioms. Country and bluegrass and folk over here, blues and spirituals and gospel over there.

So it makes sense, then, that we had to walk down a century-long hallway of “American music” before we saw the first black musician in the museum: Charley Pride, who had won an entertainer of the year award in 1971 from his song “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin.” (No shade, but the song is……straight-laced. Compare it to another song from that same year: Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On.” What’s going on, indeed).

Ok let’s pause a minute. Maybe you’re thinking, Michael, this is country music and genres are a useful way to classify things. Agreed: they can help us traverse musical landscapes. Or Michael you’re being nitpicky over some rhinestone-encrusted nostalgia. I’ll admit: I’m a recovering overthinker. But still: do you see that sleight of hand? The assumption that “Country Music Is Pure American Music,” and any other music is an optional genre? What does that do to a person? To a city? How does that history inform our tastes and inform how we treat one another?

These segregating strategies are over a century old, and it still shapes our imaginations today in small and large ways. It certainly has shaped mine. It’s why I’ve never listened to rap before (does dcTalk count..….), and why me and my youth group friends dismissed the genre because it wasn’t “melodic enough.” It’s also why The National Museum of African American Music opened in 2021 right next to the Ryman Auditorium: to reckon with an incomplete history and tell a larger, truer story of Music City. One that reflects the full diversity of the communities who call the city home.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. once said, “No human culture is inaccessible to someone who makes the effort to understand, to learn, to inhabit another world.” Inhabiting other worlds is deep in the DNA of every Still Life letter. It’s also why, from the beginning, I’ve tried to take the invitation of Black History Month seriously and make an effort to learn this art and culture in a more intentional way (check out these meditations on Coltrane’s A Love Supreme). It’s not to check a box, but to give some dedicated time to address my own ignorance. Because a long row of sequined white stars isn’t the whole story. Not even close. And the only way to discover that larger, truer American culture and history is to take small steps past our comfort zones and make an effort.

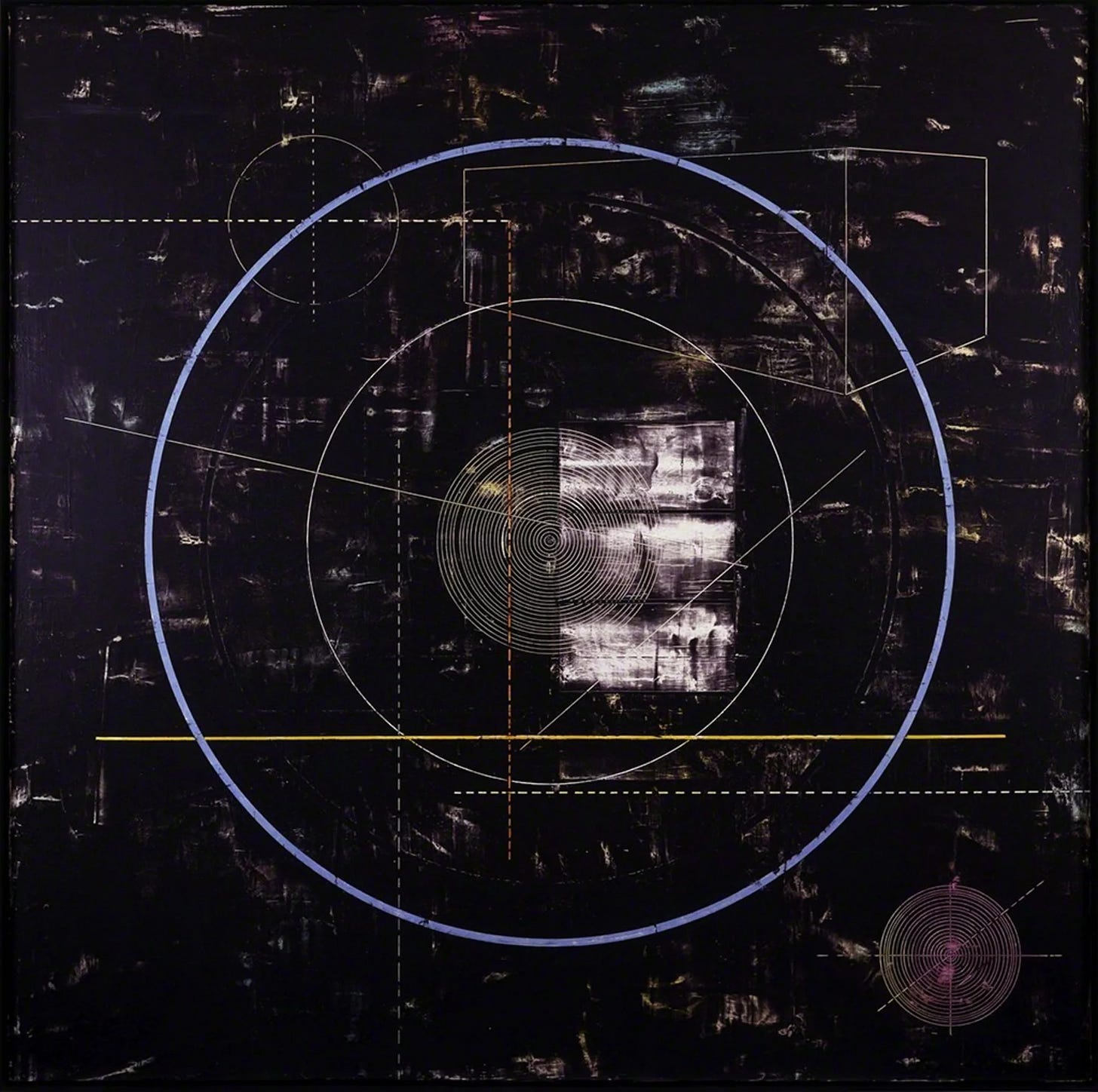

So this month, we’ll leave the Hall of Fame and walk across the street to the National Museum of African American Music where we’ll explore a recent edition to their collection: R.A.P. Ferreira’s 2020 album Purple Moonlight Pages. I’m not a rap critic, but I do know it’s by far one of my favorite albums from last year. The jazz samples! The lust wordplay! The lyrical bravado! And each song is densely layered with Black history that we can unpack throughout this month: beat poets and jazz greats, Afrofuturism, Jack Whitten’s abstract painting, Ferreira’s rap-only vinyl store Soul Folks, mysticism and the blues, and so much more.

Ferreira begins by introducing himself and the Jefferson Park Boys in the track “DECORUM.” Not “preface” or “introduction” or “overture” but decorum. What a great place to start: not just with introducing musical themes but introducing social expectations: this is how we will treat one another. After introducing the band, he directly addresses “fence-building nihilists,” calling them to “abandon them outdated strategies” of exile and hatred, to prepare their ears for what’s to come.

It could be easy to think, oh the fence-builders are the other guys. It’s those old white music execs or a politician or the country-music-machine or whatever, but that’s another sleight of hand. We don't get anywhere—I don’t get anywhere—without first recognizing how I also put up fences. I, too, can fall prey to easy nihilism where I think “oh, I don’t understand this, it’s too hard, so I don’t care.”

No. Top to bottom, we have to abandon these strategies. Self-imposed exile only gets in the way. Do you hear it? The swelling bell tone of a Rhodes piano drifts through the window and a Renaissance man calls out: “your soul writes come home.”

Take care,

Michael

“I, Too” by Langston Hughes

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.Country: The Twist Roots of Rock and Roll

Jack Whitten on his philosophies of painting

Langston Hughes at the National Portrait Gallery

Dilla Time: How the Hip-Hop Producer J Dilla reinvented rhythm